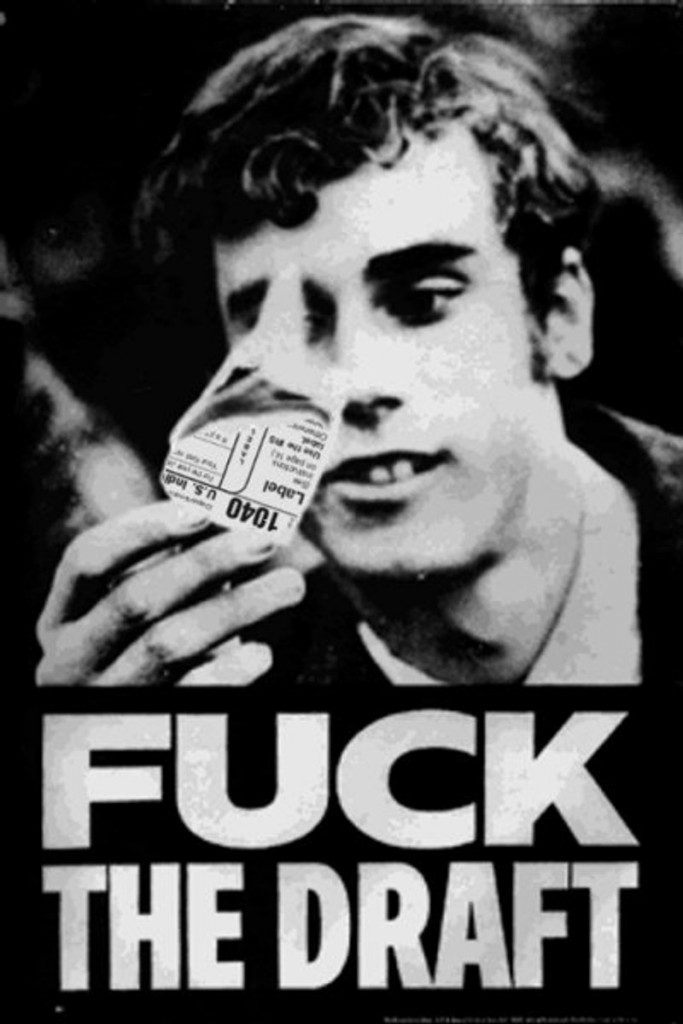

St. Louis Draft Dodger, 1969-1974

Posted by 1877 on 2015/11/05

Vietnam was one of a number of countries that private and state capitalists fought over during the Cold War. In the decades leading up to the war with the United States, Vietnam’s struggle for self-determination was comparable to Barcelona in the 1920s and ’30s in terms of strikes and social unrest. By the 1960s, authoritarian communists (lead by Ho Chi Minh and backed by the Soviet Union and China) had taken control of the north of the country, crushed any internal opposition to themselves, and were in civil war with democratic capitalists from the south (backed by their cohorts from the West).

During the war, at least 1,300,000 people were killed—over half of whom were non-combatants. Millions more Vietnamese were maimed and over 15,000,000 left homeless.

15,324,000,000 pounds of bombs (three times the amount used by the Allied Forces in World War II) were dropped by the United States military during the war. Agent Orange and similar herbicides alone killed 5,000,000 acres of forest and 500,000 acres of farmland. The dioxin-filled herbicides were sprayed in order to destroy the countryside and rural culture of Vietnam, forcing millions of Vietnamese into industrial towns to supply cheap labor for western products. 3,000,000-4,000,000 Vietnamese still suffer the (often fatal) effects of the Monsanto-made dioxins—many of whom weren’t even born until after the war.

By the early ’70s, the combined reality of unreliable and unwilling U.S. GIs in Vietnam, the tenacity of Vietnamese guerrillas, and the mass unpopularity of the war at home lead to the end of the ground war and transition to an almost entirely aerial one. By 1973, the United States had given up.

It’s hard to find exact numbers of draftees during the war, but it seems that as many as 2.3 million men age 18-25 were drafted. Of that, at least 200,000-250,000 dodged the draft or deserted the military: roughly 1 in 10 [1]. This refusal was done for ethical and political reasons but also plain self-preservation: 58,000 U.S. troops died during the war, 2/3 of which were under the age of 21. Spread out over the eight years of U.S. involvement that’s over 8,000 soldiers a year or 20 a day.

As for the military as a whole, in 1966 the desertion rate was 14.7 per thousand, in 1968 it was 26.2 per thousand, and by 1970 it had risen to 52.3 per thousand. Going AWOL was so common that by the height of the war one soldier went AWOL every three minutes. From January 1967 to January of 1972 a total of 354,112 GIs left their posts without permission, and in 1973 at the time of the signing of the peace accords 98,324 were still missing.

In 1970 alone, the U.S. Army had 65,643 deserters, roughly the equivalent of four infantry divisions. A year later the continuous refusal and mutinous behavior of troops in combat zones (along with an officer a week being killed by his soldiers) prompted Marine Colonel Robert D. Heinl Jr to remark,

By every conceivable indicator, our army that remains in Vietnam is in a state approaching collapse, with individual units avoiding or having refused combat, murdering their officers and non-commissioned officers, drug-ridden, and dispirited where not near mutinous. Elsewhere than Vietnam, the situation is nearly as serious… Sedition, coupled with disaffection from within the ranks, and externally fomented with an audacity and intensity previously inconceivable, infest the Armed Services…

As of the early ’90s, 50,000-150,000 [2] Vietnam veterans had killed themselves, and in the 20+ years since then thousands more have joined their ranks: the effects of combat still destroying and wounding those who physically survived the war. That’s right: depending on which statistics you rely on, the Vietnam War has killed equal parts to four times as many veterans after the war than during it. While suicide is growing in general with the baby boomer generation, Vietnam veterans are twice as likely to kill themselves as their non-combat counterparts. Of the 22 veterans who kill themselves a day and the over 8,000 a year [3], 70% are 50 or older. And though this number (like most of these statistics) is almost impossible to quantify, of the 3,500,000 homeless people in America, 805,000 are veterans—and nearly half served during the Vietnam War.

GIs who were stationed in Vietnam during the war are twice as likely to get lung cancer and 5-7 times more likely to develop brain tumors or pancreatic cancer than their civilian counterparts—almost certainly because of being exposed to dioxins like Agent Orange.

In 1973, the draft officially ended—do to the large-scale unpopularity of it and the refusal of so many who it affected. By 1974, President Ford offered a conditional pardon to draft dodgers and three years latter Carter offered a full one. The United States military is now 100% ‘volunteer’ (even during the Vietnam War 75% of combat troops were ‘volunteer’) and finds its cannon fodder by manipulating and coercing large pools of poor and working people.

For more information about GI Resistance during the Vietnam War

GI Resistance in the Vietnam War

Harass the Brass: Some notes toward the subversion of the US armed forces

The Olive Drab Rebels: Military Organizing during the Vietnam Era

The following is an interview with a St. Louis draft resister taken from Hell No, We Won’t Go!: Resisting the Draft During the Vietnam War. It seems clear from the account that living underground for 4-5 years was not easy and took its toll on the resister, but many who experienced combat were killed or scarred physically, emotionally and psychologically for life. Though statics about Vietnam draft resisters would be almost impossible to gather, it would be interesting to see who has fared better: those who saw combat or those who risked life underground. We assume those who chose resistance, but also know there are far too many factors involved.

NOTES

1. The 2.3 million estimate is based on 25% of all military personnel during the war being draftees, but draftees may have accounted for less than 25% of the over-all military at the time. In reality a lot less may have been drafted meaning more than 1 in 10 refused service.

2. The United States government insists this number is as low as 9,000.

3. This statistic of veterans killing themselves is almost identical to the number of GI fatalities during the Vietnam War.

When I was a junior [at Riverview Gardens] high school, they had a ceremony for a friend of mine who had dropped out of high school to join the Marine Corps and died in Vietnam, and they erected a flagpole in his honor. I felt that was a big waste, part of this war that didn’t make any sense—he died in Vietnam for a real stupid cause. One night, we took a bunch of tires and threw them over the flagpole and filled the flagpole with them so they had to cut them off. It was our way of rebelling against the situation. It was pretty much when I realized I wasn’t going to go. It didn’t make any sense to me, why people should have to fight to resolve a conflict.

I graduated in 1966, and continued with my education to stay out of the draft. I went to junior college in St. Louis. I was an art major, doing photography. Then I came to Los Angeles and studied at the Art Center College of Design for a year. When I came back after the summer, they had lost my student loan papers, so I found myself in this whole process of being drafted. Not having a lot of money to hire lawyers and all of that to try to get out of it, I ended up going to the L.A. draft counseling clinic (at the L.A. Free Clinic), and was following their advice. I went to some doctor, who gave me some papers saying I had a sinus condition, sinusitis. Then I went for my first physical, and I remember them saying, “Oh, we know about this doctor, working with the L.A. Free Clinic draft counseling. Good luck, kid.”

I went back to the draft clinic, and they said to go see this psychiatrist. I went to see him, and also took group therapy to develop a case of passive-aggressive behavior—in other words, I was a pacificist, but if I was pushed into the Army, I might kill my superiors. I came with that, and they said, “Well, we know about this guy too…. If you’re the kind of guy who would kill his superiors, you’re probably the kind of guy we want.”

The draft counselor suggested that to stall it, I keep transferring for a while, so I transferred to San Francisco, then to St. Louis, then to L.A. I remember my thoughts, going into different draft boards, seeing these kids all lined up there: I felt like screaming to them, “Look, you a have a choice in this situation!” But they were like sheep, going through whatever the people told them to do; they weren’t really thinking for themselves.

They sent me my final papers after I went through the physical, and I was supposed to show up for induction. Basically, they just gave a party and I didn’t make it—somehow I “forgot.” I went to England with a girlfriend, and another friend and his girlfriend. We were living there about nine months. I was doing photographs for underground newspapers in London, and for album covers. I stayed there until one night when my friends went out for cigarettes. The cops asked them what they were doing and found out they were Americans; they asked them for their passports, which they didn’t have, so [the cops] came back to the flat with them to see their passports. I was in bed, and the police showed up and shone a flashlight on me. They made me get out of bed and get my passport and then they found out that I had overstayed my visa, so they told me to get out of the country.

I came back to the States. I was really paranoid about getting through customs. I got into New York and saw these lines where they were checking these big books, so I got in the line with the longest-haired gut I could find. I remember going up to the counter, and he asked me if I’d been to Turkey, Pakistan, Nepal—all these places where there was hashish—and I said I hadn’t been to any of those countries. He said, “Too bad—you should have gone!” I got through.

I took a flight from New York to L.A., and from L.A. to San Francisco, and I took a bus to Santa Rosa, California, and landed there about two in the morning. I saw this cabdriver and said, “I want to go out to the Russian River,” and gave him the address [of my friends]. He drove me all the way there, about thirty or forty miles, for which he charged me five bucks.

I stayed in this little town called Forestville, redwood country, with my friends. I thought I was in paradise—it was beautiful. I had a free house to live in, [courtesy of] some friends who had gone to Mexico. I started doing a lot of artwork, painting, and drawing from nature. I changed my name to Gary Jones. I got low on money, and tried to get some welfare, but that didn’t work out too well.

I met some people that owned a theater in Petaluma, and I started working for them, doing construction work with the owner under the assumed name. One time I was driving this guy’s van, which I was unfamiliar with, and I backed into a big Cadillac. The guy called the cops, and I called my friend, who drove up, slipped into my seat as I slid out the other door and walked. I got more and more involved with the theater, doing set design and photography, performing in some operas.

The war was dragging on and on, and I was tired of living in the underground, tired of the situation in the United States, so I decided to go to Europe and check out Sweden. I had no problem getting out; [I] still had the same passport. I went to Sweden, and didn’t like that all so much. I had friends in Germany, so I stayed there most of the time. While I was over there, the whole Watergate thing was happening on TV, so the political climate was changing—we were sort of gearing out of war. Finally, I ran out of money and it was time to come back. Things were starting to cool down, so I got a driver’s license under my own name and was resuming my life. I figured things had cooled down enough where it was no problem.

About a year later, I drove up to the theater [in Petaluma] on my motorcycle, and this woman who works there came running out and said, “The FBI was just here looking for you, and they left a card if you’d like to be in touch with them.” Not really wanting to communicate with them all that much, I immediately split to a friend’s house on the Russian River, my heart racing like crazy, until I mellowed out. At that time, I was married, so I came back to where I was living, in this condominium, and spent the night. The next morning, I was pretty mellow, drinking a cup of coffee with the door open, and I see these two guys in suits walking through the gate. I took my coffee and went and sat on the bed with my heart racing. They rang the doorbell and split. I figured it was time to get out of dodge, so I went up to Mendocino for the weekend and stayed with some friends, had a good time.

I called a friend who was involved with the Quakers, and he gave me the name of a draft lawyer in Berkeley. So I went down and I saw him the next Monday. I was so petrified that my wife was doing all the talking—he said, “Is this your mouthpiece?” He gets on the phone, finds the name of the FBI agent, and asks the guy to “call off the heat,” like I was this big criminal. He said, “If they’re that close, you might as well turn yourself in.” I made an appointment to surrender myself in front of a federal judge. I got myself a white linen suit and a white panama hat, white shoes. The agent who booked me was this little short Italian guy; the judge looked like an English judge with powdered wig. He told me he’d let me out on my own recognizance as long as I didn’t take a powder.

In the meantime, I was going to have to go back and face charges in St. Louis, which was my home draft board. I found out that they had my picture on TV, along with another draft evader, in St. Louis. My mother sent me this clipping that said that the St. Louis draft board was the worst one in the whole country—they were putting conscientious objectors away for five years—so the whole idea of going back there didn’t sit well with me. My father was a Marine, and the whole time I was evading the draft, he was really down on what I was doing. But at this point he actually started protesting with a sign, which I thought was great—my father was coming around. I was all set to have to go back there, and then Ford pardoned Nixon and gave this alternate-service amnesty for draft evaders. I said, “Let’s go for it. I don’t want to have to go back to St. Louis—I’d rather deal with it here.”

The criteria [for amnesty] was that I was supposed to find a job for two years in some kind of public-service work. I looked around for a job: I looked at helping retarded kids, good-works kinds of projects, and I couldn’t find any that were available. Then I remembered that the theater I’d been working at was a nonprofit organization, so I was going to have to work two years in the theater. The lawyer got it down to one year.

In the first weeks of my employment there, there was a government car in the parking lot one morning, with a woman driving, She said, “I’m looking for so-n-so—I understand he works here.” I said, “Yes, this is where I work.” I showed her around the theater, showed her the seats I was building, some of the stained-glass windows I had done, and finally gave her a couple of tickets to the show I was going to be in. I never heard from her again. About a year later, I get this certificate in the mail with an eagle on it, saying that I had completed this alternative service.

I feel like I could have been doing more constructive things, career-wise, during that part of my life I learned a lot, but there was a lot of paranoia, too. It was kind of a waste, but there was a reason to be doing what I was doing. It was passive resistance. I just hope we’ve all learned something from the whole experience. There’s no draft now, thank god, and let’s hope it stays that way. Let’s hope that politics swings a little more to the left—it was a lot more fun than it is now, I think.