What Mound Have Been

Posted by 1877 on 2016/05/22

What Mound Have Been is a petite, personal history of the curious earthworks of North St. Louis. The text explores the mysterious origins and unexpected transformations of the city’s monumental earthen mounds from the burial grounds of Native Americans to the platforms of early St. Louis colonialists for their self-aggrandizing fountains; from a hideout for delinquent youths to modern industrial usage and its toxic remnants. What Mound Have Been strikes a balance between humor and history, poetry and prose.

The text itself is taken from the 2014 booklet Vacant Quarter. Other parts include facsimile reprints of old newspaper articles about the mounds and poetry. Digital copies are available here, and hand-made hard copies are available at aboulder.com.

WHAT MOUND HAVE BEEN

The region comprising St. Louis, Missouri and East St. Louis and Cahokia, Illinois was formerly (approximately 600-1100 AD) a large population center for Native Americans, considered by some to have constituted a city. These prior inhabitants are broadly labeled Mississippians by archaeologists, after the Mississippian culture, and Cahokians specifically. Their self-appellation is unknown to us, but their descendants likely included Siouan and Caddoan speakers.[i]

They were agriculturalists and mound builders, and the mounds were BIG. If you’re from the St. Louis area, you’ve probably been to Monk’s Mound, the largest at the Cahokia mound group. If you’re not from around here, you likely haven’t seen or heard of the mounds, despite the area having been, at one time, the center of the largest civilization north of Mexico. There has been a longstanding unwillingness among later European-descended settlers to both see and accept the earthworks for what they are, and a tendency to downplay their significance.

Some viewers, however, were struck by the impressiveness of planning, labor and scale inherent to the mounds, and several of these viewers were prominent enough to give public voice to these sentiments. In 1811 Henry Brackenridge took a long walk (by modern standards) from East St. Louis to Cahokia, following the Cahokia Creek. He wrote a letter to his friend Thomas Jefferson back east describing the many mounds he encountered, exclaiming “What a stupendous pile of earth!” when he came into sight of Monk’s Mound.[ii] He published an account in the St. Louis newspapers, and was surprised when no one noticed or cared. (What up, apathy!)

Most citizens didn’t seem to give a whit about the mounds, as Edmund Flagg, a man who visited in 1838 noted: “It is a circumstance which has often elicited remark from those who, as tourists, have visited St. Louis, that so little interest should be manifested by its citizens for those mysterious and venerable monuments of another race by which on every side it is environed.”[iii]

In 1819 a steamboat called “The Western Engineer,” en route to the upper Missouri on a scientific expedition, broke down at St. Louis. Presumably bored, the stranded Major Stephen H. Long (of the U.S. Typographical Engineers), Titian Ramsay Peele (who later became a somewhat famous naturalist) and Dr. Thomas Say (a zoologist) measured and mapped the St. Louis mound group as they waited for their steamboat to be repaired.

Said they: “These tumuli…are twnty-seven in number, of various forms and magnitudes, arranged nearly in a line from north to south.”[iv] In addition to mapping the mounds, they also tried to “dispel a misguided newspaper account of a race of pygmy moundbuilders.”[v]

Besides those who didn’t care much for the mounds one way or another, there was another large contingent of citizens who were impressed by the mounds, so much so that they refused to believe they could have been built by Native North Americans. The mounds were variously attributed to the Ten Lost Tribes of Israel, the Welsch, the Toltecs, Hindus, or Vikings [vi], with most believing them to have been built by some sort of European race who were then violently displaced by the Indians. Ephraim Squier and Edwin H. Davis surveyed hundreds of mounds as members of the American Ethnological Society and published their findings in several books associated with the Smithsonian Institution (wherein they called Indians “those hostile savage hordes”). Squier and Davis maintained that the mounds required “a degree of knowledge much superior to that known to have been possessed by the hunter tribes of North America.”[vii]

As Bilione Young puts it in her book with Cahokia archaeologist Melvin Fowler, “If Europeans could convince themselves that the savage Indians were, in reality, interlopers who had overrrun a prior advanced civilization, one founded by fellow Europeans, then they could feel justified in their persecution of the Indians and in the destruction of Indian cultures.”[viii]

Still others thought the earthworks to be natural landforms left by retreating glaciers and windblown loess soil. [ix] I read one letter written to a 19th century newspaper that defended the native people, attributing the mounds correctly to their labor, but only because they believed mounding earth does not require much skill or intelligence. Basically, racism prevailed.

The question of origins was finally laid to rest in the early 1920s, after both auger borings and cross sections were made of Monk’s Mound and conclusive reports published. This deliberate effort by both geologists and archaeologists finally brought undeniable “proof.” Such proof had to be offered before efforts at permanent preservation could make any headway.[x]

MOUND CITY

Of the three population centers, the most excavation and research has been done at Cahokia, both because it was the largest grouping of mounds/settlement, and because a city was not built on top of it, as is the case with St. Louis and East St. Louis (although flattening of mounds for farmland and interstates certainly had comparably destructive effects on sections of the Cahokia settlement). At St. Louis, mounds were scattered all over what is now the city, including two groupings on the River Des Peres in Forest Park that were destroyed in preparation for the 1904 World’s Fair.[1]

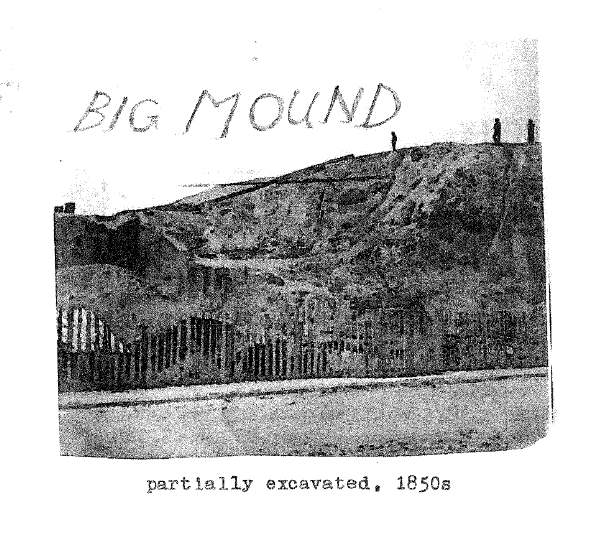

The densest mound grouping was north of downtown and close to the Mississippi River, with 25 or so mounds organized around a central plaza. The most notable were “Falling Garden,” which had a terraced side, and “Big Mound,” the unimaginatively named biggest (these names of course being given by the Europeans). Most of the mounds were destroyed as the city developed and they began to be seen as obstructions.

The internal contents of the mounds went mostly unexamined (or at least unrecorded) during their destruction. But when Big Mound was finally completely dismantled after a period of gradual earth removal, the Reverend Stephen Denison Peet (who was the editor of the American Antiquarian) was present taking detailed notes. Big Mound, he wrote,

“…was found to contain a sepulchral chamber, which was about 72 feet in length, 8 to 12 feet wide, and 8 to 10 feet in height; the walls sloping and plastered, as the marks of the plastering tool could be plainly seen. Twenty-four bodies were placed upon the floor of the vault, a few feet apart, with their feet towards the west, the bodies arranged in a line with the longest axis; a number of bones, beads and shell seashells, drilled with small holes, in quantities sufficient to cover each body from the thighs to the head.” [xi]

This type of burial, with select individuals covered in what was likely a cape made of tiny shells, is similar to some excavated at Cahokia (Mound 72, especially), [xii] and is taken by some archaeologists alongside other evidence (like the apparent sacrifice of young women whose diets seemed to have been poorer than the status individuals [xiii]) to indicate a stratified society wherein some members were ascendent over others—possibly enough so as to either compel or coerce the building of the earthworks.

I don’t really want to go into too much detail about the competing theories on Cahokia’s social/political structure (although they are very interesting), both because I don’t totally understand them and because they are best thought of as works/stories in progress—they’re bound to change and then change some more. [2]

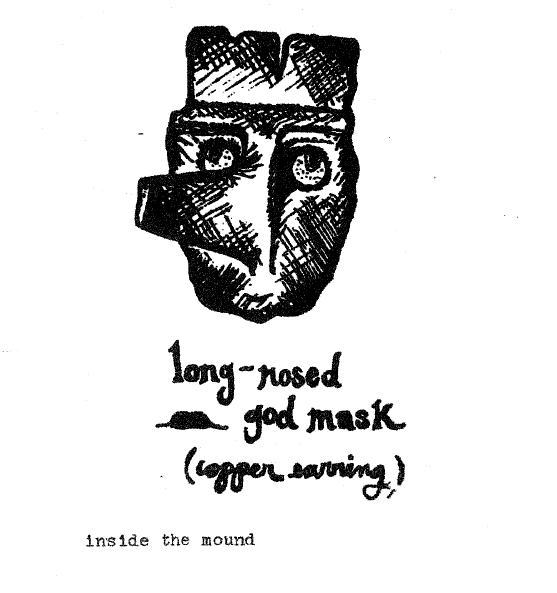

The “dig” at Big Mound also uncovered two copper earrings still in the skull of one of the skeletons. [xiv] They were about 3 inches tall and 1.5 inches wide, in the form of a “long-nosed god mask,” the nose of the face protruding 6 inches. This “long-nosed god” figure is apparently a common one, appearing in multiple locations during the “early phases of middle-river Mississippian culture history” [xv] and has been linked to oral histories of existing tribes. It is possible that this long-nosed-god is someone called “Red Horn,” aka “He-who-wears-human-heads-as-earrings,” a character who wins ballgames against giants, among other things. [xvi]

The earrings were photographed and then given to Washington University, where they were rumored to have found their way into a janitorial closet and were eventually lost. The other artifacts from Big Mound were donated to the Academy of Science of St. Louis, and the building that housed them burned that very year, 1869. [xvii]

And so the material artifacts of the mound builders of St. Louis cannot be seen or examined. The mounds themselves cannot be touched or walked on (except for the one remaining mound in St. Louis, called “Sugarloaf Mound,” which is on South Broadway, has a house built atop/into it, and was recently purchased by the Osage Nation).

There was a memorial boulder at the former site of Big Mound, at the intersection of N. Broadway, Brooklyn and Mound Streets. The memorial boulder was laid by the “National Society of Colonial Dames of America in the State of Missouri” in 1929 and used to bear a metal plaque that said “This boulder stands near the site of the great Indian mound, leveled about 1870, which gave to the city of St. Louis the name ‘Mound City.’” [xviii] The plaque is long missing, presumably scrapped. Priorly I would sometimes stop by to look at the boulder that remained on its platform, but now, as of 2013, it is gone too.[3]

WHITE MEN AND THE MOUNDS

When St. Louis was still largely theoretical lines on a map, the mounds were coveted real estate for powerful citizens of St. Louis. There must have been a lingering sense of the mounds as a seat of power, possibly as simple as “a place to look down from.”

In the early 1800s the sort of people that streets are named after—Governor Alexander McNair, General William H. Ashley, Mrs. Ann Mullanphy Biddle, and Colonel Elias C. Rector (the fourth postmaster)–all built homes on or amongst the mounds. General Ashley installed St. Louis’s first fountain atop “his” mound, contracting with the city to have free water delivered to his fountain from the reservoir. This reservoir was built on top of “Little Mound” in 1833, “the water being forced up to the tank by a steam engine on the banks of the river, and subsequently distributed by pipes throughout the city” (Hoffman 1835).[xix]

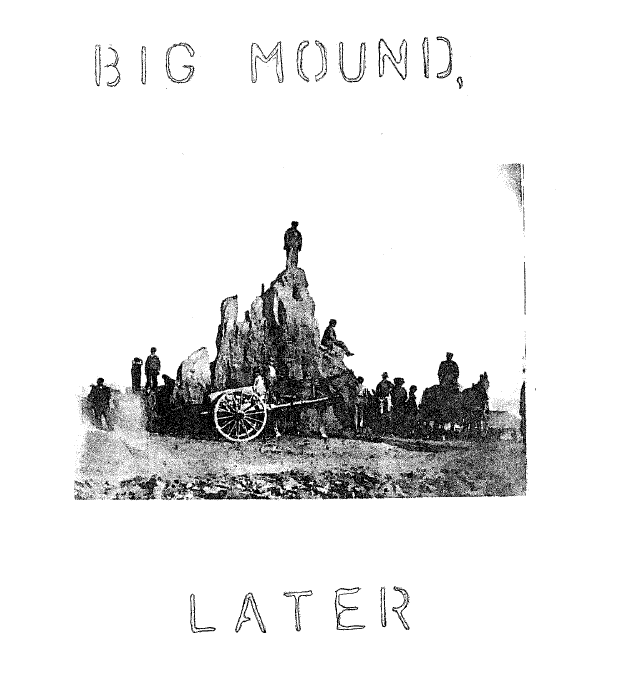

In 1844 the lumber merchants Field and Vandeventer built the Mound Pavilion, a “pleasure resort” on Big Mound. This eating and looking establishment “intended to receive all parties at all times,” but burned in 1848 after a few years of business. Bloody Island, the famous spot in the Mississippi River where politicians and prominent businessmen would meet to duel to the death, stood opposite Big Mound. [4] After Thomas C. Rector (a relative of Elias Rector, the postmaster who owned mound property) killed Joshua Barton in their famous duel (I say “famous” without ever actually knowing why did they want to shoot each other to death) on Bloody Island, he waved his hat from the west side of the island to let his relatives who looked on from Big Mound know that he had survived the duel.

Later, during the Civil War, martial law was declared and river traffic shut down. Those loyal to the Union held a demonstration atop Big Mound. [xx]

When the wealthy men abandoned the mounds, they were put to use by truant youths. As told by the newspaper of the day (whose exciting eyewitness-to-and-possible-participant-in-a-crime writing style is preserved in the Evening Whirl of present day St. Louis):

CITY CAVE DWELLERS

QUEER HIDING PLACES WHICH BAFFLE THE POLICE

Eighteen or so years ago the then adventurous boys of North St. Louis burrowed into the sides of the Indian mound that stood on Broadway in the vicinity of Brooklyn street. On stormy days and in wintry weather the boys would crawl into these caves and amuse themselves. When boys were missed from the old Mound or Webster schools and suspected of being truants a search of these caves was made by the police and most of the missing ones would be found. On one occasion a policeman, who is now on the force, had occasion to search the holes, and to do so crawled into one of the tunnels where he heard some boys singing. He succeeded in getting part of the way in when he became wedged in and could not get out. The boys discovered him and made their exit through another tunnel, and then commenced to

BURY THE OFFICER

Some men working in a brick-yard east of the mound went to the officer’s rescue, and had to fight the boys who assailed them while they were dragging out the half-buried man. The officer was taken out half-smothered. The boys were all arrested and given a severe reprimand by the justice of peace. After this adventure the police would smoke the cave-dwellers out when the truants were wanted. [xxi]

And so the citizens of St. Louis put the mounds to use for their varying whims and schemes; certainly countless unrecorded views were taken in from atop the mounds.[5]

Eventually though, speculators prevailed, those for whom a money-making potentiality is always more valuable than an existing but economically void function (such as a mass grave, a visible marker of past histories, or a place to take in views).

A FUNNY FEELING; NORTH BROADWAY NOW

Way back when steamboat traffic slowed, North Broadway began to deteriorate from an important market district into the disjointed and somewhat seedy strip it is today. [xxii] St. Louis began its emptying out and decline earlier than other cities whose fates have been similar. When the steamboats went, and after a brief but self-conscious jockeying with Chicago for railroad and regional economic supremacy, St. Louis began to lose its citizens and its vigor. Today this area of Broadway is a marginal zone, bound by Interstate 70, the railroad tracks, the bike path, the river, and finally Madison County (it and East St. Louis being wholly nother marginal spaces that exist for many St. Louisans only as places not to go).

The businesses that line N. Broadway tend to have intriguing names and indeterminate functionality—St. Louis Elevator Company, Shady Jack’s “biker’s paradise” (definitely functional), St. Louis Game Company (whose emblem is a pinball machine beneath the arch), S&B Candy and Toy Company, Missouri Gospel Announcer’s Guild, St. Louis Community Release Center (the jail one sees if sitting on a bench at the memorial boulder, under the bridge), Crystal Grill (since 1946), Apostle Wrecking Co., Grossman Iron and Steel Company, Survivor City (“home of the soul survivors”), E.H. Glueck and Co. Christmas Tree and Nursery Stock, Cash’s Scrap Metal and Iron, a jarring and plasticky Day’s Inn, Produce Row (where much of the city’s produce makes its entry and where you must go at night if you wish to buy anything)[6], East Coast Lounge and Restaurant (WARNING: SMOKING ALLOWED HERE) and Pure Pleasure Adult MegaCenter (in whose vicinity I am inevitably tailed by men in cars, despite having never seen another woman, prostitute or otherwise, walking on N. Broadway).

The space between N. Broadway and the river is a holding place for industrial substances, mounded as they await transferal via barge, train or truck. Sometimes these mounds are covered with plastic domes or sheeting, but are commonly left open to the elements. Thus the oppressiveness of particulate-heavy air—to be on the riverfront trail (or your front porch!) in a windstorm is to inhale bits of metal, salt, coal, silt and other unknown chemical compounds.[7]

I certainly do get a sort of “funny feeling” in this area. Stephen Denison Peet wrote of the area stretching along the riverfront, up to Alton:

It is said that there are caves in various localities, hidden away among the rocks. The bluffs surrounding the valley are strangely contorted. The lakes and ponds in the midst of the valley had formerly a wild, strange air about them. Agriculture was followed here, for agricultural tools have been taken from the ground in great numbers, but it was agriculture carried on in the midst of wild scenes. There must have been a dense population, for it is said that the plow everywhere turns up bones in great numbers, and the sides of the bluffs are filled with graves, in which many prehistoric relics have been found. There is no place in the Mississippi Valley where so many evidences of the strange superstitions which prevailed in prehistoric times are found.[xxiii]

Despite the xenophobic tone of his interpretation, Peet was of course correct that the region had been densely populated. By “agriculture carried on the midst of wild scenes” I assume he means that the entire landscape was not given over to agriculture, although he can only be conjecturing. Only fairly recently has it become clear that Native Americans did in fact “control” or modify the land extensively. Because of the massive loss of life and displacement of Native Americans caused by disease and murder that both preceded (in the case of disease) and followed the advancement of Europeans across the country, such land usage was often invisible to the colonizers. European settlers might pass through an area that had been modified by centuries of burning and cutting of forest and field, and being both unfamiliar with the vegetation patterns and seeing few to no residents, assume it was untouched or uncultivated.[8]

All of this is to say that while Peet’s account of the “wildness” (as lack of cultivation) of the area is not particularly to be trusted, I do find these qualities of wildness, strangeness and the sense of things hidden to be true of the area to this day.

Nowadays the mysteriousness of the landscape may be a lingering effect of the the dissolution of the mounds, compounded by the invisibility of culprit in the subsequent built environment. Rapid change makes the past difficult to discern; there is no place for historical memory to accumulate and reside. And so histories become invisible.

As Tim Pauketat puts it in his book Ancient Cahokia and the Mississippians:

In the mid-continent and Midsouth, history cleansing occurs through the total modification of the landscape. The new ethnocentric version of history is inscribed directly into the landscape with bulldozers, bellyscrapers, and dump trucks. The past is merely an obstacle to the future. It is a history of expanding markets and capital developments created by grading away the natural contours, Indian mounds and ancient habitation sites of ages past.[xxiv]

INVISIBLE ACTORS

Alongside the unknown actors of industry, others toil in attempted obscurity. Someone is always trying to rush something through (exactly who is often unknown to citizens) too quickly and without regard for the past—even the rather near past, which is still acting on the present.

Paul McKee’s massive development plan—ill-formed, impractical and presumptuous—currently looms, near to where the mounds once stood. He and those like him seem possessed of magical powers of ignorance—that is, the will to ignore. He is speculating with land that is currently occupied, and commonly by people who have been continually forced out of their homes. The lineage of displacement of poor black St. Louisans proceeds—from the Mill Creek Valley slum clearance to Pruitt-Igoe and then further into North St. Louis upon Pruitt-Igoe’s failure.

ENDNOTES

- This destruction seems paradoxical, as the fair displayed indigenous people from all over the world, made to perform versions of their cultures in reproductions of their normal environs, with a “St. Louisan lurking behind every tree.”

There was, however, a trolley at the fair running visitors to and fro the mounds at Cahokia, which were apparently such a hit with the tourists that they denuded all trees at the mounds of their leaves–to be pressed in scrapbooks as mementos.

-

The storyline presented at the Cahokia Interpretative Center, however, has not changed for some time. The “City of the Sun” narrative seems to bear little relation to current work on Cahokia. The last time I went into the center, the person at the door asked if we knew where we were going and my sister said yes, if it’s the same as before. He laughed and said “Oh it is, we don’t have money to change anything!”

Also in my more cynical moods I think of archaeology as writing the histories of those who can’t talk back—a sort of un-challengeable colonization of the past. The storylines may reveal more about the archaeologists and their current era/ideology than about whomever they are trying to understand. Which is not to say I don’t appreciate their work—clearly I am a nerd for this stuff. And of course most archaeologists are aware of the inherent impossibility of ever fully knowing what happened before.

-

I found the boulder. Beneath the new bridge and overlooking the jail is a sort of dismal parklet that houses the boulder and a new, blandly worded plaque. Although I was somewhat annoyed that the previous and bizarre boulder monument had been disappeared, the new and hidden memorial provokes the question, why bother? Also, they changed the street name from “Mound” to “Mounds.” This may be an attempt at historical accuracy.

-

Bloody Island was later joined to East St. Louis when Robert E. Lee engineered the re-routing of the river, which had been gradually moving away from the existing waterfront at St. Louis. To me this re-routing has always seemed symbolically important—as a foreshadowing of both the prioritizing of the well-being of St. Louisans over East St. Louisans and as a sort of seed of institutional violence planted early by St. Louis politicians, which grew into the ravaged and overlooked landscape that exists in E. St. Louis today. The latter being somewhat fanciful, I know.

-

To mention a couple uses of the mounds at Cahokia, past and present:

In 1809 French Trappist monks lived on Monk’s Mound, after which it gained its current name. They slept on stone and dug a shovelful of earth from their future graves each day, in addition to trying, with minimal success, to sell or trade watches to the citizens of St. Louis.

In May 1923 the Ku Klux Klan held a rally on Monk’s Mound. 12,000 KKK members showed up, planted an American flag and burned a cross atop the mound, and later took a celebratory midnight drive through Collinsville, honking and cheering, enrobed.

Nowadays if you visit Monk’s Mound at dusk, the stairs to the top are occupied with exercisers clothed in all variety of sweatsuit and spandex, rapidly ascending and descending the mound in the eternal pursuit of fitness.

-

Produce Row is also where most of the non-local produce at Soulard Market comes from. Apparently the secret to the shockingly low prices at Soulard is that whenever a refrigerated truck or train car (“from ALL OVER THE COUNTRY,” according to my source, who is prone to drama) loses power, or some other misfortune causes the produce to become less desirable/monetarily valuable, it is sent to St. Louis, where “they know they can get rid of it.” I had been wondering for years why a pineapple might be available for 25 cents in St. Louis, Missouri.

Also, according to another source, as Produce Row is directly downwind of Cash’s Scrap Metal, it receives a great amount of metallic dust onto the property. Apparently the first task Monday morning on the row is to clear the office desks of the previous week’s accumulated dust. A light dusting of metals on your 25 cent pineapple!

-

Several years ago I began hearing rumors about men in protective suits removing radioactive material from the riverfront. At the Branch Street entrance to the riverfront trail there is now a large section of earth marked with flags saying “caution, radioactive material.” Which radioactive particles…well, you know, probably move around.

Also slightly further upriver the Proctor and Gamble soap factory releases both a soapy fragrance into the air (which gives me a headache if I tarry too long in the area) and suds into the river. Directly downstream from the factory is a very popular fishing spot, where I have seen fishermen happily pulling some very large catfish from the river.

-

The Cahokians, however, were long gone before any Europeans showed up.

REFERENCE NOTES

i. Pauketat, Timothy. Cahokia: Ancient America’s Great City on the Mississippi. 2009. (37-38)

ii. Brackenridge, Henry M. Louisiana. http://olivercowdery.com/texts/1814brak.htm.

iii. Marshall, John. “The St. Louis Mound Group: Historical Accounts and Pictorial Depictions,” The Missouri Archaeologist, Vol. 53, December 1992.

iv. “Old Broadway: A Forgotten Street and Its Park of Mounds,” Missouri Historical Society Bulletin 4, April 1948.

v. Pauketat, Timothy. Ancient Cahokia and the Mississippians. 2004. (174)

vi. Ibid.

vii. Fowler, Melvin L. and Biloine Whiting Young. Cahokia: The Great Native American Metropolis. 2000. (30)

viii. Ibid. (31)

ix. Marshall.

x. Fowler and Young. (34)

xi. Peet, Stephen Denison. The Mound Builders: Their Works and Relics.

xii. Pauketat, Cahokia… . (101-102)

xiii. Ibid. (133)

xiv. Ibid. (143-144)

xv. Pauketat. Ancient Cahokia…. (114)

xvi. Ibid. (115-117)

xvii. Marshall.

xviii. Marshall?

xix. Ibid.

xx. Ibid.

xxi. ?

xxii. Ibid

xxiii. Peet.

xiv. Pauketat. Ancient Cahokia. (175-176)

Filed under General