George Caleb Bingham and The Verdict of the People

Posted by 1877 on 2017/01/07

Trigger warning: This article contains details of lynchings and other graphic violence necessary in maintaining slavering.

This article is written in response to the petition attempting to halt the St. Louis Art Museum from loaning The Verdict of the People to Donald Trump’s inaugural luncheon. The petition reads,

“George Caleb Bingham’s 1855 painting ‘Verdict of the People’ has been selected to be present at Donald Trump’s inaugural luncheon in Washington, D.C. in January. We the undersigned express our objections to the loan by the Saint Louis Art Museum and request its cancellation.

‘Verdict of the People’ depicts a small-town Missouri election, and symbolizes the democratic process in mid-19th century America. We object to the painting’s use as an inaugural backdrop and an implicit endorsement of the Trump presidency and his expressed values of hatred, misogyny, racism and xenophobia. We reject the use of the painting to suggest that Trump’s election was truly the ‘verdict of the people,’ when in fact the majority of votes—by a margin of over three million—were cast for Trump’s opponent. Finally, we consider the painting a representation of our community, and oppose its use as such at the inauguration.

Art can be used to make powerful statements. Its withdrawal can do the same. Join us in our campaign.”

The problem is the picture does depict “a small-town Missouri election, and symbolizes the democratic process in mid-19th century America”, one I imagine has much more to do with modern Democracy and the supposed values of Trump voters than the mythical ideal of American equality: white supremacy and misogyny.

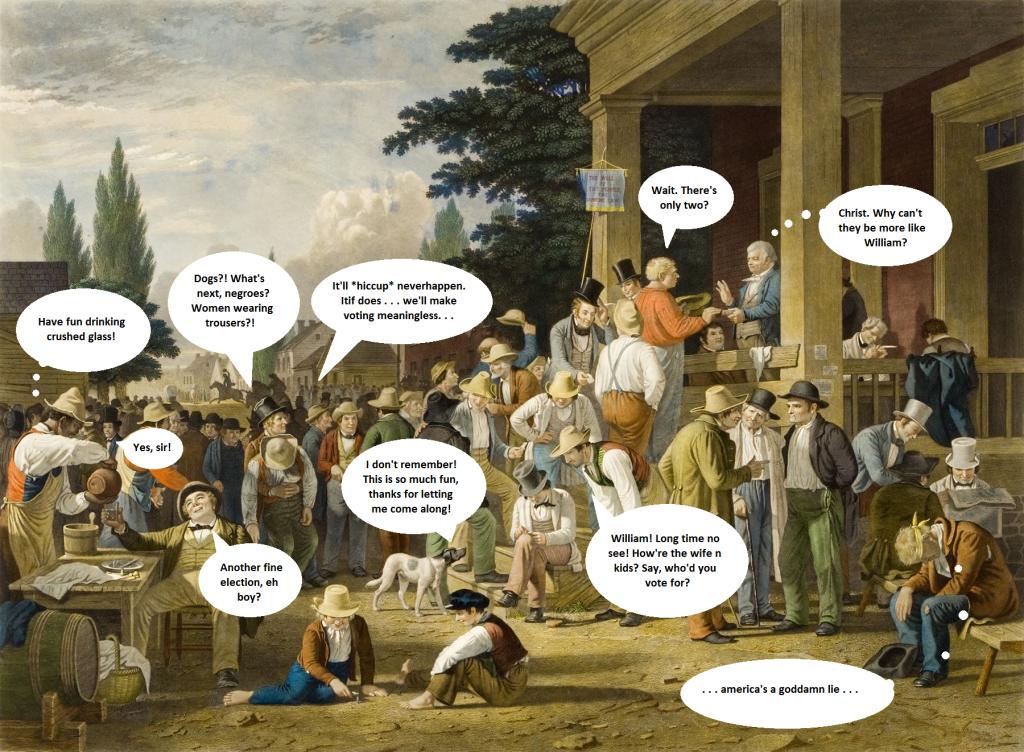

In the first of Bingham’s Election Series, The County Election, no women are present. The only person of color is a slave serving drinks. Literally, a stray dog gets more representation and perhaps say in the matter. Bingham intended the piece to express his views on Universal Suffrage, which based on the painting meant only white men. The next in the series, Stump Speech, affirms Bingham’s depiction that politics is the realm of man and his best friend. The only non white male in the image (and you really have to strain to even know she’s there) is a near silhouetted woman in the background. She appears to be turned away from the speech, and, if anything, tending to a man.

The County Election, 1852

Finally there’s the Verdict of the People. The painting is once again overwhelming white men cheering, arguing, and getting to have a say in how society is run. People of color and women are almost entirely absent. In this way it’s a telling picture of America then and now. The only women depicted are onlookers. They’re small and far off, possibly even cheering on their own subordination as Bingham would have it. Even if we’re optimistic, if any of these women were 18 in the painting, they’d be 84 by the time Democracy let them vote. The only person of color, a black slave, doesn’t even get the day off! (He’d be 34 by the time of the 15th Amendment, and 111 when the Voting Rights Act tried to protect his right to vote.) One might suspect a subversive bent to the painting, the one I’m inclined to see of American Democracy’s true colors based on the will of white men. But I suspect this is our modern gaze projecting it, for Bingham likely accepted if not championed these very values we object to in Trump and so many other places. Bingham’s failure to condemn Democracy as racist and misogynist is underscored by the fact that he does criticize the wild, drunken and messy aspects of voting—more an across the aisle jab at his Jacksonian opponents than anything else.

Let’s have a closer look at the world George Caleb Bingham inhabited in order to better understand what Democracy might have meant to him.

Bingham was born in Virginia in 1811 to a slave owning family. The Binghams moved to Franklin County, Missouri in 1819 during an incredibly turbulent time both racially and politically. The area they settled was known as Boone’s Lick, later to be called Little Dixie. For the last five or so years, Sacks, Foxes, Osages and other Native people had skirmished and fought small battles against encroaching white settlers. Though abandoned by the British after the War of 1812, these warriors kept fighting. Sadly, waves and waves of white settlers like the Binghams eventually proved too much. Hunting grounds, seasonal Native villages and wilderness in general was all slowly transformed into plantations of the Anglo-American tradition.

Around the time the Binghams arrived, Missouri was demanding statehood. But the introduction of Missouri as a slave state would off-set the balance of “free” and slave states, the federal government argued, and they would have to intervene. Slave-owning Missourians were enraged: no previous state had had it’s constitution meddled with by the federal government. Their right to craft their own constitution (and the enslaving of people of color that it allowed) was their god-given right. Boone’s Lick is where this topic was most fiercely debated.

At a Christian camp meeting in Howard County, a white man named Humphrey Smith stood up and condemned the practice of slavery. He even went so far as to challenge a Mr. Sexton, demanding to know how he could be both a Methodist and a slaveholder. Other slave owners quickly rushed to Sexton’s defense claiming, “God [has] made negroes for slaves, and white men for masters, or he would not suffer it to be so!” Smith’s proclamation was met with extra ire since he and his wife Nancy were rumored to help runaways. The accusation is likely true. Assuming their fate as slaves was about to be sealed by statehood, a number of people had recently taken matters into their own hands and run off from their Boone’s Lick masters. These runaways added to the seasonal practices of day to day runaways. The Smiths possibly aided this recent wave.

A month after the meeting, the Smiths were visited at night by a masked mob which dragged Humphrey from the home and beat him with clubs. If not for the intervention of Nancy who knows what the crowd might have done. Throwing herself into the melee, Nancy had her eye knocked out in her successful struggle to save her husband. She remained blind in it for the rest of her life, a price she was willing to pay to end slavery. Not only were those who attacked the Smiths never prosecuted (you can imagine why), but Humphrey Smith left Howard County a few days later a fugitive having been charged with inciting slaves for his speech at the interracial camp meeting.

Bingham’s father, a slave owning judge in the next county over, likely did little to aid the Smith’s in their ordeal. One assumes he looked the other way or cheered their departure—so much for the American political process or blind justice. Eight months later, the Howard County candidate running on the States Rights ticket (read: the pro-slavery ticket) gunned down his opponent. The local court ruled it an illegal duel and nothing more. According to Humphrey’s son, “A war of extermination was waged by the Pro-Slavery party” of Howard County against those who opposed them. Such was the atmosphere and sense of Democracy young Bingham imbibed.

When Bingham’s father died in 1823, the family moved west near Arrow Rock in Saline County. Just four years before, knowing he realistically had little to no legal recourse, an 18 year old in Saline named Frank had killed his abusive master. Frank was caught and sent to St. Louis to stand trial, but escaped before being executed. Whether he was recaptured is unknown.

Bingham spent the next 20 years based out of Arrow Rock, frequently traveling to St. Louis and points in between for work. During this time he owned at least three people, while his family owned at least twenty more. When Bingham officially moved to St. Louis in the 1840s, it had become a slave’s best chance at freedom—of course not from any help of the democratic process, which only tightened its hold on the slave population. No, St. Louis was a place to hide, blend in or find a friendly river worker to smuggle you north because of people of color’s own subversive networks and the sheer size and anonymity of the city.

In 1836, Francis McIntosh, a free man of color working on a steamboat docked in St. Louis, helped a shipmate evade the police. Another version of events says he merely stood by and refused to help the arresting officers—an illegal act at the time when involving the arrest of a black person. In response the two cops arrested Francis and told him he would soon be lynched. Fearing the worst, he stabbed the two and ran, though tragically was re-arrested and taken to the St. Louis jail. A few hours later Francis was extracted by a mob and burned to death at what is now Kiener Plaza. During the half hour it took the blaze to kill him, an alderman (a democratically elected official), stood armed over the proceedings, threatening to shoot anyone who intervened—even for the purpose of putting Francis out of his misery which he begged the crowd to do.

When Elijah Lovejoy spoke out against the lynching in his paper, a mob destroyed his press. Lovejoy died shortly after defending his third and final press from another pro-slavery mob across the river in Illinois. Despite being a free state, racism and white supremacy did not respect the boundary.

Stump Speech, 1853-1854

Five years later when a group of four river workers—free and enslaved—were caught robbing a local bank during which they killed its clerks who served as night guards, 15,000-30,000 people flocked to the city to watch their legally sanctioned execution. National scorn and shame had been heaped on St. Louis after the extralegal killing of Francis McIntosh, so local officials were determined to repair the city’s image—that and restore the state as the rightful executioner of rebellious black people. Former Mayor Daniel D. Page sat on one of the juries. Eight years before while serving as St. Louis’s second mayor, Page had beaten his slave Delphia within an inch of her life. The timeline is fuzzy, but Page may have even been re-elected after the incident. Page was also known for chasing his slaves around his yard and publicly beating them. You can imagine how other members of his household were treated. Out of all four juries for the 1841 burglars, the longest deliberated half an hour.

As the crowds gathered to view the hanging, extra scorn was heaped on Charles Brown, the abolitionist of the group who’d helped countless people escape north via his river work connections. In addition to increasing his standard of living, Brown had used theft to fund his abolitionism. Brown viewed slaves stealing from their masters or black people from rich whites as a way for people of color to compensate themselves for the unpaid labor of slavery.

When dropped from the scaffold, Brown’s noose failed to break his neck (rumored to have been intentionally set to fail). So he too, like McIntosh, took half an hour to die. Afterward the four’s heads were placed on display in a local pharmacy’s window as both a lesson to any who dared transgress Missouri’s legally and divinely sanctioned racial boundaries as well as proof of the mental inferiority of black people and their proclivity to crime and immorality.

When Bingham arrived in St. Louis for good, not only could most people of color not own property, marry, live where they chose, be free, drink alcohol, gather in public or private, sell goods or leave their master’s property without his permission, but reading and writing had been officially outlawed as well. All of this brought to you by Democracy in general and specifically that of Missouri which Bingham chose to memorialize. Once again, these laws were certainly broke, but only because of subversive customs formed by people of color. Black people’s fulfillment of their day to day needs and desires brought them relief, not Democracy.

By the time Bingham got himself elected to the Missouri legislature in 1848 he saw slavery as a doomed system, though was hardly an abolitionist and likely still viewed whites as superior. When legislation was introduced to give Missouri more control over its slaves, Bingham countered with a law giving the federal government control. While the modern reader may see this as a step in the right direction, half measures like these end up perpetuating atrocities like slavery, not ending them. Assuming Bingham may have wanted to phase out slavery, his faith in the federal government was naive at best since it had only ever capitulated to pro-slavery sentiments. Over the next six years, the federal Fugitive Slave Act and the Kansas-Nebraska Act would help the expansion of slavery and the re-enslavement of self-emancipated slaves. Who knows what other racist laws Bingham helped pass or uphold.

In the 1850s Bingham was critical of both Missouri slave owners and Kansas abolitionists, eventually growing to despise some of the latter. During the Civil War, Bingham stayed with the Union and publicly condemned those who left it, though this doesn’t mean much since Missouri was allowed to keep its slaves. When General Frémont, head of the Department of the West based out of St. Louis, issued the very first Emancipation Proclamation freeing any Missouri slaves whose masters gave aid to the Confederacy, Lincoln was enraged. Frémont was quickly recalled by the Great Emancipator (and most successful third party candidate in U.S. history, what-what!) who promptly sent Missouri slaves back to work. When Lincoln issued his own Proclamation sixteen months later, he made sure to keep 500,000 slaves (those whose masters remained loyal to the Union) in chains. In reality, this mattered little to Missouri slaves, since thousands of them were already looking to themselves for freedom by running away. One estimate says as many as 50,000 Missouri bondspeople had run off within the first nine months of the war.

Bingham ended his white supremacist, patriarchal career as Kansas City’s first police chief, inheriting the mantel of Missouri’s slave patrols, or pattyrollers.

So hated and feared, one Missouri slave prayed nightly, “Oh, Lord, we thank thee for the new Jerusalem, with its pearly gates and its golden streets, but above all, we thank Thee for that high wall around the great big city, so high that a patterroller can’t get over it.”

These examples of people confronting and fleeing slavery or transgressing Missouri’s racial boundaries are filled with protagonists who continually found themselves at odds with the democratic process: racist voters, politicians, judges, police, clergy, jailers. All of which broke the law when it failed to serve their white supremacist dreams. Slavery was not incidentally to the 200+ years of American life it was allowed—it was integral to it. And along the way, Democracy made itself perfectly compatible with it. One might say it would have failed without it.

Perhaps William Wells Brown while running away from St. Louis with his mother in 1833 said it best, “As we travelled towards a land of liberty, my heart would at times leap for joy. At other times, being, as I was, almost constantly on my feet, I felt as though I could travel no further. But when I thought of slavery with its Democratic whips—its Republican chains—its evangelical blood-hounds, and its religious slave-holders—when I thought of all this paraphernalia of American Democracy and Religion behind me, and the prospect of liberty before me, I was encouraged to press forward, my heart was strengthened, and I forgot that I was tired or hungry.”

I appreciate the petition’s attempt to engage Trump’s inauguration, but to call the painting “a representation of our community” is ill-informed. It would be one thing if the scene depicted was subversive or documenting a moment of rebellion—say a scene from bleeding Kansas in the 1850s, or August Chouteau’s slave in 1802 trying to burn his mansion to the ground (the largest in St. Louis and seat of regional power) or when his brother Pierre’s slave successfully did burn the latter’s three years later. Or if Bingham were an actual champion of human rights or equality and had bothered to paint, say, a Mother Baltimore—these would be images we should fight to keep from Trump’s clutches. But the fact of the matter is that this painting celebrates some of American Democracy’s core beliefs: white supremacy and patriarchy. What could be more fitting for Trump’s inauguration?

The Verdict of the People, 1854

Filed under Gender General Race