St. Louis, 1910: Brown Family Moves to Forest Park Heights

Posted by 1877 on 2015/08/25

In the summer of 1910, the Brown Family moved to Forest Park Heights, an all-white suburban neighborhood southwest of Forest Park. Immediately, residents protested their arrival. Louis Brown had bought the house on the 7500 block of Wise Ave (modern-day Richmond Heights) for himself and his family—including Lela Warwick, a school teacher, four cousins, and at least four other members. Brown was a Pullman porter and had saved wages and tips to buy the house.

The story of the Brown Family in Forest Park Heights—cut up and abbreviated by the fact it has been pieced together by old Post-Dispatch articles—sheds light on the legal and vigilante ways racial housing segregation was enforced in St. Louis in the early 1900s.

At the time, residents racistly assumed Brown could not afford the house himself and that he was part of a scam to make them buy the property from him at a profit. Brown and Warwick appear to have been part of the black middle- to upper-working class. Together with eight other family members, Brown might have very well bought the house with savings. Once threatened, Brown did say he would sell the house for a profit. Whether this was premeditated is impossible to discern. If it was thought out, it’s a cool hustle: black family buys house in all-white neighborhood for $5000-7000, racist residents freak out, family says they’ll sell for $10,000.

Regardless of whether the Browns honestly moved to Wise Ave for a home and were forced to defend themselves or by themselves or with a third party were trying to scam Forest Park Heights, the Brown Family drama is captivating and insightful.

We’ve compiled a series of articles, originally published in the Post-Dispatch in 1910 and 1911, about the Brown Family’s struggle against the racial order of that time. Included in italics along the way are our thoughts and interpretations of the articles, intended to provide depth and call into question the racist and classist assumptions of the original articles. Be warned: this story includes racial and white supremacist violence—main ingredients in creating america, st. louis and capitalism and ones used everyday to keep them functioning.

Post-Dispatch, August 13, 1910

Louis A. Brown, a 24-year-old Pullman Porter, having saved the price of a $7000 suburban home from his tips, has installed an arsenal in the house to defend his family against white neighbors who object to his presence in Forest Park Heights.

“Some very nice white gentlemen called on me the other day,” Brown told the Post-Dispatch reporter on Saturday, “and told me that there were some bad people in the neighborhood that objected to my family being here, and that they were afraid they might not be able to control those bad people.”

“I told them it didn’t make any difference to me whether they controlled them or not, and that they needn’t go to any trouble on my account, for I wasn’t afraid of bad people.”

Has Arms and Ammunition.

The smiling young negro pointed to two Winchester rifles, one of which lay in the corner and the other on a bed, and to a shotgun on the floor.

“There are also three revolvers in this house, and plenty of ammunition,” he added.

Brown, who has a run on the Burlington Railroad, is away from home two-thirds of the time, but his fortress-home is manned by four other men, whom he described as “cousins of mine.” There are also two women and a boy, besides Brown’s immediate family, which consists of his wife and mother. The house has five rooms.

Brown declared that he had purchased the place outright and that he will not sell for less than $10,000. Residents of Forest Park Heights, who have organized a committee to deal with the situation created by his presence, believe the purchase was made on the installment plan, and some of them say they doubt whether more than $10 was paid down.

Previous Effort to Sell Made.

Albert Turner, who formerly occupied the house, recently offered to sell it to Edward Meyer [who lives across the street at 7522 Wise Avenue]. Meyer did not wish to buy, and the announcement of the sale to the negro soon followed.

The neighborhood committee, which consists of Meyer, C. H. Bauer, W. D. Williams, John Conway and Gus Lindenstein, will hold a meeting to decide some action. Forest Park Heights is about a quarter of a mile west of West End Heights.

The next article seems to use the committee Meyer established in the previous article and the Forest Park Heights Improvement Association interchangeably. If they are the same group, it means that the Forest Park Heights Improvement Association had at its origins a mission to enforce white supremacy. If you’ve ever suspected that your neighborhood association’s obsession with cookie-cutter features like overly-manicured lawns and exterior paint choices had lurking beneath a more authoritarian agenda, the Brown Family’s treatment should give some validation. Here we have an obvious example of such a group enforcing racial and class divides.

One wonders what the modern-day neighborhood associations for Maplewood and Richmond Heights do to implicitly and explicitly enforce these divides today and if there is a clear line of descent between them and the Forest Park Heights Improvement Association.

As for the committee members themselves, I can only find information about the Browns’ neighbor, Edward Meyer. About 59 at the time of all of this, he was a well-to-do butcher. By 1919 he was retired and worth $50,000.

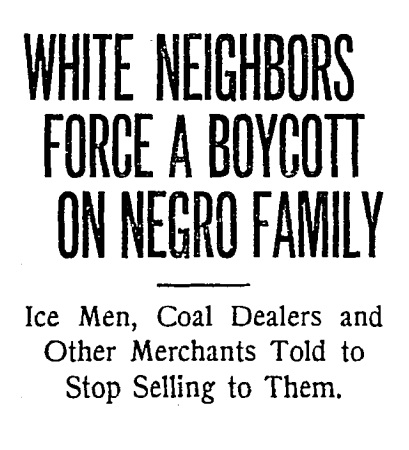

Post-Dispatch, August 14, 1910

White neighbors of Louis A. Brown, a Pullman Porter, who purchased a $7000 home in Forest Park Heights with his savings from tips, put into effect a boycott yesterday which they expect will result in Brown and his family moving from the neighborhood.

Delivery men on ice wagons were notified that they must refuse to deliver ice to the negroes. It was intimated to them that any company which sold to the negroes would find itself without customers among the 100 members of the Forest Park Heights Improvement Association. One member said the same rule would apply to coal deals, and that the negroes would be prevented from laying a supply of coal to last through the winter.

Every druggist, grocer, butcher and tradesmen for many blocks in every direction of the house is to be notified, according to W. D. Williams, one of the members of the association, that nothing shall be sold to the negroes.

Brown Asks $10,000 for House.

Brown was in a peaceful mood last night and did not exhibit the two rifles and shotgun, which he showed to a reporter yesterday morning, saying significantly that he was not afraid of being “run out” by force.

“No boycott will get us out of here,” said Brown last night. “We buy all our provisions downtown anyway, and are not dependent on these little stores out here.

“I bought this house and intend to stay here unless I can sell it for $10,000. That is the least I will take.”

Many members of the improvement association say they believe Brown was hired to move into the house with the expectation that a large price would be paid to get him out. These members say they do not believe he owns it.

The house is occupied by Brown, his wife and mother and four men, who, he says, are his cousins.

On December 2, four people attacked the Brown home with gunshots and a brick. I can find no articles from the time about it—only a recap of the events at the end of the following article. It mentions a “tumult” that followed the attack in which the four attackers were able to escape. I wonder, by “tumult,” does the article mean the Browns came outside and stood their ground, possibly shooting back? Does it mean curious neighbors poured from their homes creating a chaotic scene and a crowd of people that the attackers were able to disappear in? We don’t know. The Post would have reasons for reporting and not reporting the Browns defense either way.

If similar to modern-day journalism, the Post might have followed this pattern. Before event: x is violent and capable of anything. After event: nothing happened, it was all a lot of talk. Mentioning potential violence before the fact lays the ground work for any police or vigilante violence or repression to be justified. Reporting that nothing happened after the fact (even when someone or a group has defended itself or successfully attacked or sabotaged something) makes it seem like the group is ineffectual and powerless.

Conversely, the Post might have very well played up the potential and real violence of the Brown’s self-defense in general and would have loved another sensational anecdote or detail to report on.

Post-Dispatch, December 16, 1910

A house in Forest Park Heights, occupied by Lela Warwick, a negro school teacher, and Louis Brown, a Pullman porter, the sale of which to the negroes had resulted in indignation mass meetings by residents of the suburb, was destroyed by fire early Friday.

Fearing violence from his white neighbors, Brown had provided himself liberally with ammunition, and had two shotguns and a revolver in the house. The heat set off the cartridges and the fire was accompanied by a rattle as of musketry.

The Forest Park Heights Volunteer Fire Department made no effort to check the blaze and the customary alarm by ringing the school bell was not given.

Brown, the negro school teacher and her parents had been living in the house, but they are said by residents of the suburb to have left it Sunday[, August 11]. An elderly negro remained as caretaker, but he did not sleep in the house.

Fire to Give Alarm.

The fire broke out at 2:45 a.m. Edward Meyer, who lives across the street at 7522 Wise avenue [and is a member of the Forest Park Heights Improvement Association that has been trying to drive the Browns out of the neighborhood], says he was awakened by the crackling and light, and that he fired several shots in the air to give an alarm.

Mrs. Meyer said she saw three men going in and out of the house Thursday night, but thought nothing of it, because the negroes could buy no provisions in the suburb, and were accustomed to have them sent out at night from town. Mrs. Meyer thought she saw a wagon [in the] back of the house.

Rolland Hill, chief of the fire department, lives at 7420 Ethel avenue. He was awakened by the alarm, but said he did not think it worth while to try to save the house.

The house, a one and one-half-story frame structure, made such a bright blaze that it attracted the attention of revelers at Campbell’s Forest Home, a mile away, and they drove to the scene in automobiles, making merry as the flames destroyed the dwelling.

The house was built by Albert Turner, and he tried to sell it in vain to other white residents of the suburb[—specifically, Edward Meyer]. He then sold it, through a real estate concern, to Brown, accepting two deeds of trust, one for $4000 and one for $1500. Brown made no cash payment, but was to pay $40 a month until he had paid $5000, when the house was to become his.

December 2 the neighbors adopted Ku Klux Klan tactics. Four men appeared at night in front of the house and fired shots through the four front windows of the house. One of them threw a brick through another window. No one was hurt by the bullets, and the men disappeared in the tumult which followed the attack.

Forest Park Heights is about one-fourth of a mile west of Forest Park.

Post-Dispatch, February 2, 1911

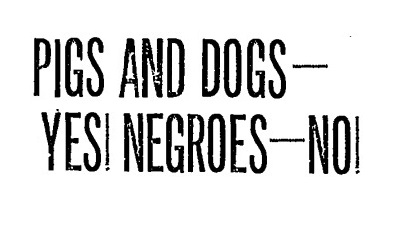

This isn’t the actual title of the article, but it might as well be. The article is only three paragraphs long and talks about a meeting of the Forest Park Heights Improvement Association held in a Clayton school. At first a motion is made to limit the number of pigs a resident can have—one pig for every 50 feet of land. But after a homeowner with a lot of pigs says he can’t afford to buy more land and doesn’t want to get rid of the pigs, a sympathy vote turns it down.

Next a motion is made for a similar ordinance, but involving dogs. After a dog owner stands up and says he’ll have to get rid of dogs, the motion is voted down.

Finally, “the only motion carried and adopted during the meeting was one that bound every property owner in the Heights from leasing, selling or renting any property or building to negroes. This motion was made on account of the result of recent trouble with Miss Lela Warwick, a negro school teacher.”

I can find nothing more about Louis or Lela, other than an article about Dr. Sebastian Klein three months later. Klein was part of the black bourgeoisie of St. Louis—being a doctor, owning a number of properties and running multiple businesses.

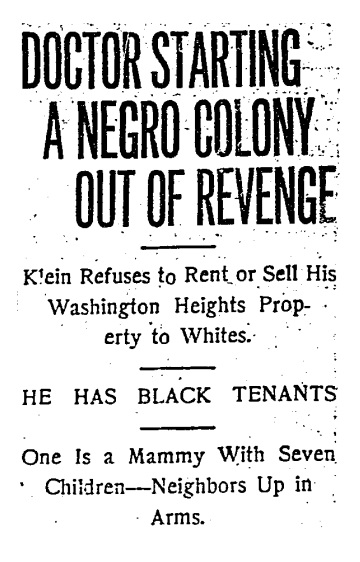

Post-Dispatch, May 19, 1911

After receiving a notice from Street Commissioner Travilla, informing him that there was building rock on his lot in Washington Heights which constituted an obstruction to the street, Dr. Sebastian Klein of 1921 North Grand avenue announced Friday that he was more determined than ever to colonize the fashionable district with negroes. He told a Post-Dispatch reporter that he had already engaged one tenant—a negro mammy with seven children.

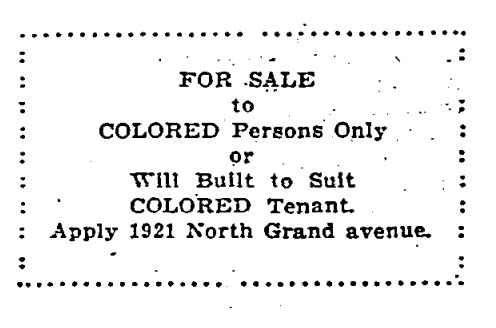

Two months ago Dr. Klein aroused the residents of Washington Heights by announcing that he was going to sell his ground on Waterman avenue, east of Skinker road, to a negro. He erected a sign 8 feet high by 10 feet at the base that reads:

Neighbors Got Injunction

The cause of the feud between Dr. Klein and the residents of Washington Heights is an injunction which they obtained against him from putting up an apartment house in the district. Washington Heights has building restrictions which provide that no structure other than a single dwelling shall be put up and the residence must not cost less than $5000.

“I knew all about the restrictions when I bought the property,” Dr. Klein told a Post-Dispatch reporter Friday. “But the point is this: There are now 20 buildings in Washington Heights. Thirteen of these are flats and the other seven are apartment houses. The restrictions never restricted until I bought ground there and had started to put $50,000 into a single and a double apartment house. There never was any charge that I intended putting stores on the ground floors of the apartment houses.”

Many Complaints Made.

“At first I was going to sell all the ground to one negro, but they have acted so mean about it that I am changing my plans a bit. They notified the Board of Health that I was maintaining a nuisance there and the Street Department that I was obstructing the street, and the Police Department never seems able to catch them trying to tear my sign down.

“You see, that makes it necessary for me to have somebody right on the ground to take of it. I am going to move some families of negroes there and let them live free on the ground until I sell it all to other negroes. I have put the matter in the hands of my lawyer, who is looking up the law to see whether it will be legal for me to build shacks for negroes who are to take care of the property, to live in temporarily.”

One negro is a Pullman porter and the other is a teacher in one of the negro schools.

Negro’s Home Burned.

Dr. Klein says the Pullman porter’s name is Louis Brown and that he is the same negro who had such a lively time when, with Lela Warwick, a negro school teacher, he took a house in Forest Park Heights. The house was destroyed by fire early one morning when there was nobody home.

Dr. Klein says that the Washington Heights Improvement Association now wants to buy the ground back from him at $10 a foot more than he paid for it, but that he is determined he will sell it to nobody by negroes.

Five years later, St. Louis voters passed a city-wide ordinance making it illegal for anyone to move onto a block where more than three-fourths of the residents were of another race. Within a year, the U.S. Supreme Court had overruled this type of ordinance, but not before a dozen other cities replicated it. Shortly after, the court did affirm the right of neighborhood associations—like the Forest Park Heights and Washington Heights Improvement Associations—to bar people of color from living in their neighborhoods. In similar cases for decades to follow, when outright legal discrimination was impossible, neighborhood associations used thinly-veiled legal language like “undesirable elements” to keep people of color and other undesirables out of wealthy, white neighborhoods.

In May 2015, Maritha Hunter-Butler, her partner and three sons moved to an all-white section of St. Charles. Maritha says shortly after they moved in they began to be harassed because they are black, and she is in an interracial relationship with a woman. Four days after they settled in, according to a police report, a neighbor called the police reporting several black male subjects “walking down the street with dogs and a couple of them are snapping pics of homes. Caller (advises) that this is an all-white neighborhood and they do not belong.”

Like in Forest Park Heights, Maritha’s neighbors wonder how she can afford the house. Most immediate neighbors have taken to personally harassing the family and routinely call the police and animal control on them. Since May, police have been called to their house 16 times. One of Maritha’s only immediate neighbors who’s trying to stay out of the feud told a Post-Dispatch reporter that “the issue could possibly be resolved if the trustees of the homeowners association would enforce the bylaws, including restricting the number of dogs to two and barring outside structures for them.”

I can find no further information about Louis Brown, Lela Warwick, Dr. Sebastian Klein or either of their attempts at living in all-white neighbors. Any additional information would be greatly appreciated.